Copa América 2019: Looking back at the rest of the tournament

Categories: Competition Analysis

In my previous post, I summarized Brazil’s triumph at this year’s Copa América. In this post, I will provide a summary of the rest of the tournament.

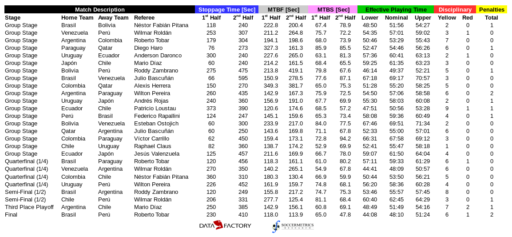

Match Quality

The Copa América was a 26 match tournament, so it’s not too much of an information overload to present match quality metrics for every match. Below is a table of metrics that referees have nominal control over, such as time added on for stoppages, mean time between fouls and stoppages, effective match time, disciplinary cards shown, and penalties given.

Unfortunately, DataFactory’s data feed doesn’t tag the moments when the ball leaves the field of play, so I can only give an estimate of effective playing time. The average playing time in this Copa América was 57 minutes 15 seconds, plus or minus about two minutes. Both matches with the greatest and least amounts of effective playing time involved Venezuela: their last group stage match against Bolivia (69 minutes 51 seconds) and the quarterfinal against Argentina (48 minutes 9 seconds). However, the final between Perú and Brazil features 48 minutes 10 seconds of effective playing time, so it’s possible that this match did in fact have the least amounts of effective time. But it’s not clear with this data set.

Over the entire tournament, the amount of time added on was 178 seconds (3:18) in the first half and 350 seconds (5:50) in the second half, giving support to the significant disparity in stoppage time given in both halves of a football match. Moreover, there appears to be a significant difference in time added in group stage and knockout matches:

| 1st Half Stoppage Time | 2nd Half Stoppage Time | |

| Group Stage | 159.1 | 344.1 |

| Knockout Stage | 222.8 | 367.8 |

There also appears to be significant difference in the mean time between fouls (MTBF) between group stage and knockout matches. The metric is consistent between halves, however. The data appear to indicate that the knockout matches were refereed more tightly, but anecdotal evidence may disagree with that observation.

| 1st Half MTBF [Sec] | 2nd Half MTBF [Sec] | |

| Group Stage | 198.0 | 218.2 |

| Knockout Stage | 161.9 | 166.1 |

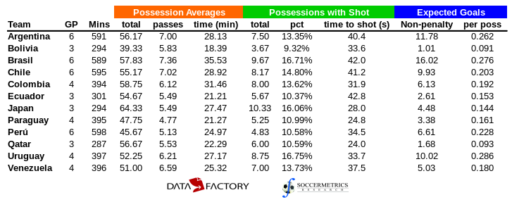

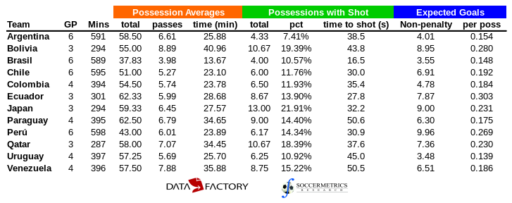

Match Possession

Match possession by a team is defined here as a sequence of two or more consecutive successful passes. The following two charts show the average offensive and defensive possession metrics for every team in the Copa América. I focused on three categories: total possessions, possessions with at least one shot attempt, and expected goals per possessions containing a shot.

Most of the teams exchanged possession with their opponents at roughly an even rate, within four to five possessions. There are some exceptions — Bolivia and Paraguay averaged about fifteen fewer possessions per match than their opponents. Brazil, to no one’s surprise, averaged twenty more possessions per match than their opponents. They also averaged more possession time than their opponents by more than 20 minutes. Bolivia experienced a similar difference in possession time, but in deficit in their case. Paraguay, Qatar, and Venezuela had 10-13 fewer minutes in possession.

Other than the national teams at the extremes in possession, it’s not possible to infer performance from possession metrics. It is possible to tease out some conjectures as to playing style and whether those styles were actually successful.

Team Review Thumbnails

Now here are my brief reviews of every team in the Copa América, aside from Brazil. These reviews will be in inverse order of final position in the tournament.

Perú: Manager Ricardo Gareca took time to find his best XI during the group stage. But when he found it — a 4-4-2 diamond with Yoshimar Yotún and Renato Tapia playing a double 6 — he stuck with his starting XI for the entire knockout phase. Their best match, by a wide margin, was the 3-0 semifinal win over Chile. It saw destructive work on the wings, clinical finishing, topped off by a virtuoso final goal by Paolo Guerrero, their best offensive player of the tournament. Yes, their xGA/90 over the entire tournament was 1.89, which wasn’t very good. But if you take away the group stage result against Brazil, their xGA/90 drops to 1.22.

Argentina: You can’t say the Copa América was a failure for Argentina. They did advance to the semifinal, they were the only side that could restrict Brazil, and they did finish third. All of these outcomes aren’t bad for a federation that remains unstable. But you can’t say it was a success, either. Once again, they failed to win an international tournament, and after two matches they showed every indication of an early and embarrassing exit. The ball found its way to Lionel Messi’s feet a lot; he was third among all players in combined xG and xA (4.97). But his output in actual goals and assists — one of each — was just not what was required, most of that his fault (especially on set-pieces, where about 25% of his kicks reached a target), some of it the fault of his teammates who converted inconsistently. Sergio Agüero, Lautaro Martínez, and Leandro Paredes were among the few that could feel good about their performances.

Chile: The outgoing South American champions chose to attack down the middle — 65% of their final third touches were in the middle sector of the pitch, a greater percentage than any other side. Chilean manager Reinaldo Rueda played the same lineup for more minutes (283) than any other side. Their defense was not as strong, but they could still mix it up physically (e.g. Gary Medel). Charles Aránguiz, Eduardo Vargas, and a surprising Alexis Sánchez were the best players for Chile.

Colombia: This team hit their heights in the group stages, excited neutrals to the point that they were imagining the cafeteros in a Copa América final, and then failed to approach that level in their first knockout match against Chile. A real disappointment that can’t be explained away by VAR or bad luck. James Rodríguez was the only Colombian player who finished in the top 20 in expected assists (12th; 1.14). Only one player, Duván Zapata, ranked in the top twenty in expected goals. In a tournament for which goals were at a premium, Colombia didn’t create enough chances from good areas on the field.

Uruguay: I really thought that this side was capable to meet Brazil in a final and being competitive. Video Assistant Referee thought otherwise, and Perú executed their penalty kicks to advance. José Giménez was one of the best central defenders in the tournament. Rodrigo Betancur was the most important to their passing network. Luís Suárez was their most dangerous player, but from a creative standpoint this time. Edison Cavani was more dangerous in front of goal. In the end, it’s a frustrating performance because Uruguay did find and take their chances, but the men in the booth spotted microscopic violations.

Venezuela: A positive tournament for Venezuela who advanced from the group stage unbeaten. There was some disappointment at losing to an Argentina side that appeared to be for the taking. Roberto Rosales was important to the Vinotinto‘s passing networks. Salomón Rondón was the only Venezuelan player in the top 40 in expected goals and assists, but Darwin Machís and Josef Martínez scored the actual goals.

Paraguay: The Albirroja preferred to concede possession to their rivals and create opportunities through direct bursts. Sometimes it worked, as it did in the match against Qatar, but most of the time it did not. Only Bolivia made fewer entries into the final third. In fact, the 2-2 draw to the Asian champions represented a missed opportunity. Miguel Almirón was their best player in the midfield, particularly in their first two matches. He was their lone player who finished in the top 50 in total xA, and he was 49th. Óscar Cardozo and Derlis González, who scored a goal apiece, finished just outside the top 20 in total xG. Paraguay did hold Brazil to a 0-0 draw in the quarterfinals, but to be honest it was a very one-sided match.

Japan: Japan treated the Copa América as an opportunity to blood younger players in a competitive environment. It’s a win-win for everyone involved — Japan obtains valuable experience for its players, and the tournament organizers don’t have to worry about the prospect of a guest nation winning the championship of South America. Japan took a lot of possessions and fired off a lot of shots, but on the whole they weren’t very good shots. Shoya Nakajima generated more chances than any other player, and Takefusa Kubo showed why Real Madrid were so quick to sign him. But Japan’s failure to win the game that both they and Ecuador had to win stood out for its ineptitude.

Qatar: Qatar also used the Copa América to gain experience for its experimental lineup. They came back from 0-2 down to salvage a point against Paraguay, they lost by the minimum to Colombia on a late goal by Duván Zapata, and exited with a 0-2 defeat to Argentina that was only settled late. The difference between offensive and defensive possessions wasn’t great, but Qatar allowed more passes per possession, more time on the ball, and more high-percentage shots. Hassan Al-Haydos was their leader in combined xG+xA.

Ecuador: Ecuador were disappointing. Their possession metrics were poor, and in opponents’ possessions that contained at least one shot, the average xG/possession was 0.30. Their attack was Enner Valencia and no one else. And the draw against Japan, in a match whose winner was guaranteed a knockout round berth, was simply inexcusable.

Bolivia: The worst team in the tournament. Bolivia played their best 45 minutes against Brazil and never approached that level of play again. They had the fewest possessions and on-ball time per match, allowed the most possessions and opposing on-ball time per match, and achieved the fewest final-third entries of any side in any flank. Their best player in terms of xG+xA, Marcelo Martins, was 56th among all Copa América players at 0.97 units (1 penalty goal). Diego Bejarano was the most important to their passing networks, and the only Bolivian player to register an assist.

CORRECTION: I have recomputed the expected assist metrics for all of the players to correct an error in the tracking of successful free kicks and corner kicks. I’ve revised the text above.

This post has been prepared with match event data supplied by DataFactory Latinoamérica.